This information sheet is provided to you to give you all the information you need to understand what a diagnosis of cruciate ligament disease means for you and your dog. It is one of the most common causes of lameness that we see in dogs and fortunately there is a lot that we can now do to treat it. This also means there is a lot of information available on the internet which can become overwhelming or confusing if you only have incomplete information. The first part of this information sheet is a summary of what the condition is, how it is diagnosed and treatment options available. If you are interested in more comprehensive information, more detail is provided in the following pages. There is also information that explains the differences between this condition in dogs compared to that in people and hence why some of our recommendations and surgical techniques differ.

What is the Cranial Cruciate Ligament

The cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) is located inside the knee joint. Its main function is to limit cranial drawer and internal rotation. When it is damaged, the knee becomes unstable, allowing the thigh bone to move backwards and the shin bone forwards in relation to one another. This produces abnormal sheer forces which damages delicate joint cartilage and the meniscus. Once damaged these structures do not regenerate and perpetuate lameness through the progression of arthritis.

How Does it Tear?

While CCL rupture can occur with excessive force causing traumatic rupture, it is more common for the CCL to rupture under normal weight bearing conditions. It is thought that this is the result of various medical and biomechanical conditions that allow chronic and progressive degeneration of the CCL. This is important to understand because for about 30% of dogs the opposite CCL is weakened by the same processes, resulting in rupture of the other CCL at some point in their lives.

Diagnosing Cranial Cruciate Ligament Rupture

This can sometimes be diagnosed in the consultation room. However, if patients are particularly painful or tense, anaesthetic and X-rays may be needed for a diagnosis. X-rays are generally recommended before a decision on the final treatment plan is made to allow measurements to be taken for surgery and rule out any other conditions causing lameness in that leg. We generally X-ray the opposite knee as well to determine if degenerative changes have occurred in that leg.

Treatment for Ruptured Cruciate Ligaments

A combination of conservative, medical and surgical treatments are used in the management of patients with CCL disease. As these patients suffer from some degree of arthritis, medications to control pain and maintain the health of joint cartilage are routinely used. However, because this is a mechanical problem, the main goal of treatment is to stabilise the knee joint surgically. We now have a range of procedures that we can perform which either stabilise the knee joint with artificial ligaments or neutralise abnormal forces in the joint by changing the biomechanics of the joint. Ultimately which procedure is used depends on the patient’s size, activity level, how torn the ligament is, how much arthritis may already exist in the joint and if there are any conformational abnormalities in the joint. Early intervention is important so as to help limit the progression of arthritis and also allow recovery of the injured leg in case the patient is unlucky enough to rupture the ligament in the opposite knee.

Surgical procedures routinely used for CCL rupture at Anstead Veterinary Practice are the Lateral Fabello Tibial Suture (DeAngelis), Tightrope procedure, Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA) and Triple Tibial Osteotomy (TTO). A more thorough explanation of these and other techniques is provided on the following pages. Following any of these surgeries, it is important to provide strict rest and confinement for a period of six weeks after surgery to ensure healing and to reduce the chance of complications.

If you have any unanswered questions after reading this information sheet, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Lameness resulting from partial tears or complete rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament represents one of the most common causes of lameness in dogs.

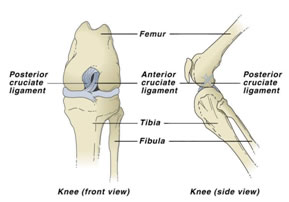

The dog’s knee (stifle) joint relies solely on soft tissue structures for its stability. The cranial cruciate ligament (CCL), caudal cruciate ligament, two menisci, two collateral ligaments and muscle tone through the quadriceps, hamstrings and calf muscle are all involved in controlling the forces acting on the knee joint. The CCL, which is located inside the knee joint is most commonly injured. It is composed of two bands that intertwine. Originating on the thigh bone (femur) at the back of the knee and extending to the shin bone (tibia) at the front of the knee, the CCL is the primary stabiliser of cranial drawer and internal rotation. When it is damaged, the knee becomes unstable, allowing the shin bone to move forwards in relation to the thigh bone. This produces abnormal sheer forces which damages delicate joint cartilage and the menisci. Once damaged these structures do not regenerate and perpetuate lameness through the progression of arthritis.

Anatomy of the dog’s knee. Note the position of the cranial cruciate ligament in the diagram on the right. This helps understand its function.

There is no single cause of CCL disease. The CCL is most commonly observed to rupture under normal weight bearing conditions and it is thought that this is the result of various conditions that allow chronic and progressive degeneration of the CCL. These include disuse, obesity, conformational abnormalities and immune mediated disease. Hence, the term CCL ‘disease’ is preferred instead of ‘rupture’, to acknowledge the involvement of these underlying factors as true traumatic rupture resulting from excessive force on the ligament only accounts for about 20% of cases of CCL disease. Unfortunately for about 30% of dogs the opposite CCL is weakened by the same degenerative processes, resulting in rupture of the other CCL at some point in the future. Pet insurance companies therefore may not cover the second knee if the policy is taken out after the first knee was diagnosed.

The x-ray on the right illustrates the significance of a steep tibial plateau angle (TPA). At the normal standing angle the thigh bone essentially wants to slide backwards down the top of the shin bone. This places excessive force on the CCL.

Conformational abnormalities that are commonly associated with CCL disease are luxating patellas (knee caps which sit out of their groove) and steep tibial plateaus (this is the slant of the joint surface at the top of the shin bone). In both circumstances, the biomechanics of the joint are changed in such a way that the CCL is placed under excessive strain. This is not only an important cause of CCL disease, it also represents important considerations for the surgical management of the condition.

Cranial cruciate ligament disease is always one of our primary suspects when we see a dog with hind leg lameness. Sometimes the condition can be readily diagnosed in the examination room by demonstration of stifle instability through a positive cranial drawer sign or cranial tibial thrust. Many patients also have muscle atrophy of the affected leg and thickening of the knee joint indicating that changes have actually developed over many weeks if not months even if owners have only noticed lameness recently.

Demonstration of stifle instability is not always straight forward as many patients will be too tense because they are nervous or painful and this will prevent the tests being performed accurately. In some cases the tests will not work because the ligament only has a partial tear or the disease is so chronic that scar tissue forming around the knee has restricted this laxity. In these situations general anaesthetic and x-rays are needed to confirm the diagnosis. Even though we cannot see the ligament on x-ray, x-rays are very sensitive at picking up secondary changes that are associated with CCL disease.

X-rays are also generally recommended before proceeding with treatment so that we can rule out other diseases like traumatic fractures and bone cancer and to take measurements to help us determine the most appropriate treatment for your dog.

Demonstration of Cranial Drawer sign

Demonstration of Cranial Tibial Thrust

Management of Cruciate Ligament Disease

Several strategies are often combined to help treat dogs with CCL disease. These can be broadly grouped into conservative, medical and surgical treatments. Surgery has long been regarded as integral in the treatment of this condition as mechanical instability is the primary problem we aim to overcome. However, conservative and medical treatments should not be overlooked in the overall management of CCL disease. These are listed in more detail in Table 1 at the end of this information sheet. Conservative management essentially includes common sense strategies to reduce force on the joints. In the short term patients should have enforced rest and as things settle down, exercise should be modified so as to not precipitate further injury. Weight management is often overlooked but cannot be overstressed. Physiotherapy is a growing area being used for dogs with arthritis and post operative rehabilitation. Medical treatments broadly cover pain killers such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and joint protective agents which come in injectable forms or as dietary supplements.

There are many surgical treatments available for dogs with CCL disease, each with their own benefits and limitations. The main purpose of this information sheet is to inform you of what surgical options are available for CCL disease. At Anstead Veterinary Practice we aim to provide you with a range of surgical options to suit individual patient and client circumstances.

The main goals of surgery are to;

- Restore stability in the CCL deficient knee

- Regain function

- Reduce pain

- Limit further development of arthritis

It is worth mentioning that some of the differences between surgical treatment for CCL disease in dogs and the equivalent condition, anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in people. Firstly, surgery in people is generally reserved for young and/or active people. Many people can compensate for anterior cruciate ligament rupture with strengthening exercises or a brace. In dogs we recommend surgery for all patients, particularly if they are over 15kg. The reason for this is;

- Strengthening exercises used for people with cruciate ligament rupture cannot be implemented effectively for dogs.

- Because such a high proportion of dogs suffer CCL disease in the opposite leg (a notable difference from the human condition), these patients can become crippled if they suffer tears in both ligaments in close proximity to one another.

- Even though many dogs under 15kg can regain reasonable limb function without surgery, many surgeons believe that the high incidence of meniscal injury perpetuating lameness warrants surgical intervention.

In humans, surgery involves using grafts from hamstring or patella tendons to replace the ruptured ligament. These techniques have also been used in dogs, however, these techniques often require prolonged periods of rest before the grafts regain adequate strength, which is not always practical in dogs. Furthermore, similar results were being obtained by using implants to replicate the function of the CCL. These procedures provide static stabilisation of the knee. In addition to these procedures, a number of new procedures have been developed principally to change to biomechanics of the knee joint and neutralise sheer force thereby providing dynamic stabilisation of the knee. The basic difference between these procedures will be outlined in the following paragraphs and more detailed information provided in Table 2 at the end of this information sheet.

Surgeries that are used to provide static stabilisation of the knee include the lateral fabello tibial suture (commonly referred to as the DeAngelis procedure) and the tight rope procedure. In both procedures a non absorbable suture is placed outside the knee joint and anchored in such a way that it mimics that action of the CCL. Good results can be obtained with these procedures. The tight rope procedure aims to overcome some of the limitations of the DeAngelis procedure where implants can break or loosen as well as facilitating the positioning of anchoring points so that they are isometric and provide more natural joint movement. These procedures are better suited for smaller dogs, dogs without conformational abnormalities and dogs without significant fibrosis in the joint.

Several techniques have been developed to provide dynamic stabilisation of the knee. Broadly speaking these techniques reduce the slope of the tibial plateau and/or change the position of the patella tendon so that the CCL is no longer required and the joint is stabilised by the actions of actively contracting muscles neutralising any sheer forces. The procedures include the Tibial Wedge Osteotomy (TWO), Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy (TPLO), Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA) and finally the Triple Tibial Osteotomy (TTO), which is a combination of the TWO and the TTA. All these procedures involve cutting the bone (performing an osteotomy) and aligning the bone in a slightly different position. Despite what sounds like a painful surgery, these techniques generally provide patients with more rapid recovery, better range of motion, are less likely to develop arthritis and are more likely to return to athletic function compared with static stabilising techniques. They have largely been the realm of specialist surgeons but are increasingly being performed by veterinarians who have been trained in the various procedures with access to specialised equipment. These techniques are suitable for larger dogs, dogs with conformational abnormalities and dogs with significant fibrosis of the joint. They are also recommended in cases where static stabilisation techniques have been unsuccessful. The decision on which technique to use is largely based on surgeon preference. More specific detail can be found in Table 2. The TTA and TTO can be performed at Anstead Veterinary Practice.

The decision on whether on not to have surgery depends on a number of circumstances. As already described, surgery is indicated for most dogs. The few exceptions would be some smaller dogs and dogs with other more significant medical problems. Age is not a limiting factor with the exception of growing dogs who should wait until they are fully grown. For many owners, finances may limit which surgery can be performed. We are always happy to discuss which options are best in these cases.

Conservative and Medical Treatments for CCL Disease

Conservative Treatments

Rest – This is particularly important when a partial tear or rupture has occurred recently. Avoiding undue exercise will avoid inciting pain and reduce further damage to the unstable joint. Exercise modification is required long term also so as to avoid the opposite leg overcompensating for the sore leg. Remember, 30% of patients will rupture their other CCL and overzealous exercise will just make this more likely.

Weight management – For many dogs this means that we simply need avoid weight gain that may develop because patients cannot exercise as they did previously. This will generally mean restricting calorie intake by reducing quantity of food or changing to a lower calorie diet. More importantly though, obesity contributes to the development of CCL disease in many patients and serious weight loss is mandatory if other treatment strategies are expected to work as well as reduce the likelihood of the opposite CCL rupturing.

Physiotherapy – This is a growing area in veterinary medicine with physiotherapists trained in the human field undertaking additional study to adapt their methods for animals. Common applications are for dogs with arthritis and for post operative rehabilitation for cruciate ligament surgery.

Medical Treatments

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) – These have remained the mainstay of managing pain associated with arthritis and musculoskeletal injuries. These are very effective drugs when used for their intended purpose, which is reducing pain and inflammation. Many patients feel better and walk better when on these medications and they form an essential component of therapy. However, they are not going to prevent the development of arthritis and they do nothing to stabilise the knee joint. In other words, they must not be considered a suitable alternative to surgery where surgery is indicated.

Cartrophen Injections – Cartrophen is a disease modifying drug given as a series of injections for arthritis. This has been demonstrated in clinical trials to;

- improve the integrity of joint cartilage and cushioning of the joint surfaces

- increase the quality and viscosity of joint fluid

- Improve blood supply to the bone underlying the cartilage helping to reduce joint pain and improve nutrition to the joint

- Cartrophen also has anti-inflammatory properties.

We have been using Cartrophen for many years with good results, however once again, it cannot stabilise the knee joint in a CCL deficient knee and should not be considered an alternative to surgery.

Dietary supplements – Nutraceuticals such as glucosamine and chondroitin have been used for many years for joint protective and mild anti-inflammatory actions. There are products formulated specifically for dogs. Fish oil supplements used by people for arthritis are not thought to have the right concentration of omega-3 fatty acids to have the same benefit in dogs. Hill’s Prescription Diets has overcome this by formulating a diet with high concentrations of Eicosapentaenoic Acid from fish oil which helps reduce the production of cartilage degrading enzymes, thereby helping to maintain joint function.

1. Static stabilisation procedures

Lateral Fabello Tibial Suture – One of the most widely performed surgeries used today is the lateral fabello tibial suture, commonly referred to as the DeAngelis procedure. There are several modifications to this procedure but the underlying principle is the same. A non-absorbable suture is anchored around the fabella behind the knee and is passed through a bone tunnel in the front of the shin bone. This does a very good job at mimicking the CCL and can be performed by most veterinarians with minimal specialised equipment. Its main disadvantages are that the implant eventually breaks or loosens. Much of the remaining stability is provided by scar tissue around the implant.

Tight Rope Procedure – This is a modification of the lateral fabello tibial suture. The tightrope procedure makes use of bone tunnels and specially designed implants that not only reduce the chance of the suture breaking or loosening but more importantly allows specific placement of the suture in more natural (isometric) points.

2. Dynamic stabilisation procedures

Tibial Wedge Osteotomy (TWO) – Developed by Barclay Slocum, the TWO was the first of these dynamic stabilisation techniques developed. It involves removing a single wedge of bone from the front of the shin. When the bone is realigned the net effect is to flatten the tibial plateau slope. The main disadvantage of this procedure is that depending on the size of the wedge removed, the shin can be significantly shortened and other aspects of knee function could be negatively affected.

Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy (TPLO) – Recognising some of the limitations of the TWO procedure, Slocum modified the technique by removing a semicircular cross section of bone isolating the tibial plateau fragment from the tibial tuberosity and aligning it so as to flatten the tibial plateau angle. This overcame the shortcomings of the TWO. Slocum took the unusual action of patenting this technique so only those who undertook his course were allowed to practice the procedure and were not allowed to teach it to others. Due to limited numbers of courses many specialist veterinary surgeons were unable learn the technique, leading them to explore and develop the following techniques.

Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA) – This adopts a different approach to achieve the same effect as the TWO and TPLO. The protuberance of bone which the patella ligament attaches to on the shin (tibial tuberosity) is cut and fixed in a more forward position. The goal is to have the patella ligament 90 to the tibial plateau. This is able to effectively neutralise sheer force. One of the main advantages of this procedure over other dynamic stabilising techniques is that is less invasive, not requiring an osteotomy through the main weight bearing axis of the shin bone.

Triple Tibial Osteotomy (TTO) – This approach has adopted principles of the TWO and TTA. The effect is to produce the same effect with less dramatic alteration of angles and therefore results in less alteration of the normal anatomy of the knee.